Imagine that you can’t see and hear, and your environment seems to consist only of things within reach. How might you feel, and how would you communicate? What might happen to your sense of security?

For those who live without sight and hearing, the world can feel like a solitary and confusing place. Their senses of smell, touch, taste, and balance become their bridge to the outside world.

What Is Deaf‑Blindness?

“Deaf‑blind” is the name of a disability category included in the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). IDEA identifies children with deaf‑blindness as having auditory and visual impairments that together “create such severe communication and other developmental and learning needs that [students] cannot be appropriately educated without special education and related services, beyond those that would be provided solely for children with hearing impairments, visual impairments, or severe disabilities.” Deaf‑blindness is rare; in fact, according to the 2019 National Deaf‑Blind Child Count, there are only about 11,000 children with the diagnosis who receive special education services in the United States.

Some people who are Deaf‑blind may have lost one or both senses due to an accident or illness, but most are born with the condition because of hereditary syndromes, prenatal complications, or prematurity. Almost 90% of children with deaf‑blindness have one or more additional disabilities, with the most common being cognitive impairments, physical impairments, and complex medical needs that often result in medical fragility.

Vision Loss

Some people with deaf‑blindness have complete vision loss. Others may be considered “legally blind,” which means their vision cannot be corrected to better than 20/200 in their better eye, or their visual field is 20 degrees or less in their better eye. Some others may have a cortical visual impairment (CVI), which is a neurological disorder that affects visual processing and is not an organic eye problem.

Hearing Loss

Not all people with deaf‑blindness have total hearing loss. Some have hearing that improves with hearing aids or cochlear implants. But even when these supports are provided, hearing is never completely restored.

Some people with deaf‑blindness have a central auditory processing disorder, which occurs when there is no loss of sound sensitivity, but sensory information is not processed adequately in the brain.

Living with Deaf‑Blindness

For people who are Deaf‑blind, both hearing and vision loss are significant, and when combined, they present barriers that are unique and formidable.

Development

Development challenges usually begin in infancy and continue through adulthood.

Visual Learning

When most infants get to know the world around them, they do so primarily with their eyes. As infants begin to roll and crawl, visual objects draw their attention and promote mobility and exploration of the environment. This, in turn, facilitates development of cognitive, social, motor, and language skills. Infants who are Deaf‑blind use their hands; their senses of smell, taste, and balance; and body awareness to learn about their environment. They learn and develop, but in a very different way than their peers with sight and hearing.

Functional Language

By the time a child develops vocal language, they have heard thousands of spoken words and sentences, and they have a fairly large receptive vocabulary. Children who are Deaf often have parents who use American Sign Language (ASL), and those children learn language at a similar rate as hearing children. As infants, they begin to imitate sign language the same way babies with hearing begin to babble. Children who do not hear or see language miss this important part of language learning, so they lag far behind peers in developing functional language.

Incidental Learning

Have you ever observed or listened to someone and suddenly realized that you had a big misconception about something? Maybe it was knowing what to wear at a certain event or understanding a certain concept. This kind of incidental learning is often missing for children who are Deaf‑blind, which causes deficits in social, functional, and academic skills. As a result, these skills must be explicitly taught, and learning them is dependent upon a functional method of communication.

Isolation

Isolation is a reality for many people who are Deaf‑blind. Helen Keller said, “Blindness separates a person from things, but deafness separates him from people.” If personal interaction is limited to the area defined by the arm’s reach, that interaction ceases when a person moves outside of that sphere. An added challenge is that many people are uncomfortable with physical touch, and in the age of COVID‑19, physical closeness is often prohibited. When remote learning became the norm during the pandemic, students with complex needs like deaf‑blindness were often left out.

Communication

Some people who are Deaf‑blind read and write braille. Others may use tactile sign language, in which signs like those used in ASL are made on the person’s body or hand. And some may use tactile or visual symbols or objects, or even simple physical touch, to communicate. Behavior also functions as communication, especially when no other options exist. Often, when problem behavior is analyzed, it is found to be functioning as communication of wants or needs in people with no other means to deliver those messages. A functional behavioral assessment is sometimes needed to figure out what message is being communicated by the behavior. It’s important to watch for attempts at communication in nontraditional ways and shape those attempts into functional communication.

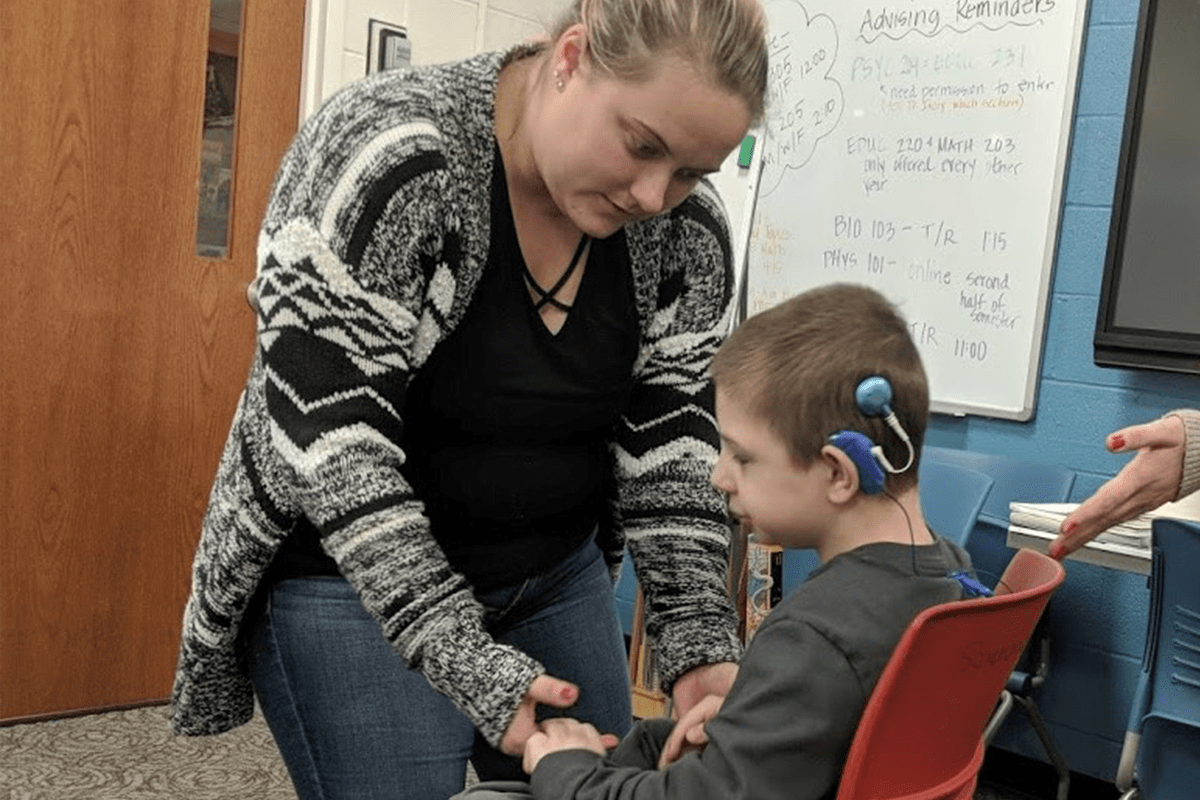

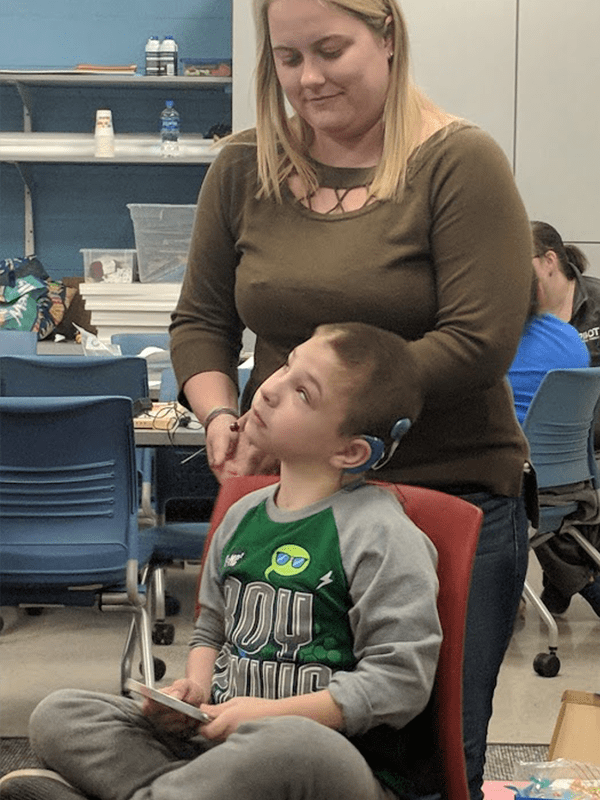

Hand‑under‑Hand Prompting

Remembering the importance of the hands in children who are Blind can help us to understand why it is important to use hand‑under‑hand prompting to support and teach learners who are Deaf‑blind. Hand‑under‑hand prompting means the student places their hand on top of the teacher’s, after which the teacher performs a task or guides the student to a certain place, object, or tactile symbol. Think of this as the child listening and looking.

When a child’s hand is resting on top of someone else’s, the child is in control of what they do just as a typical person is in charge of where their eyes look or what they listen to. While it might require more patience for the prompter, it is more respectful to the person being prompted.

For example, you would not take another person’s face in your hands to force them to look at a certain thing; this would be considered intrusive and inappropriate. Yet this is similar to preventing a person from “looking” with their hands by using hand‑over‑hand instead of hand‑under‑hand prompting.

Example of Hand‑under‑Hand Prompting

In the classroom, hand‑under‑hand prompting might look like this: When a student is sorting math manipulatives, his intervener might prompt him by bringing her hands under his, guiding their hands to the box of manipulatives, and then sliding her hands out from under his. Alternately, the student would have the option to move his hands off the intervener’s hands at any time, with the intervener respecting the student’s choice and waiting to take his lead.

The Team

Those who teach, care for, and love someone who is Deaf‑blind know that they can be a lifeline to the outside world. While there are many types of individuals who make up a cohesive team for a person who is Deaf‑blind, the following people are especially helpful.

Family

The child’s family should be involved in forming the educational and communication program every step of the way.

Interveners

These people receive special training to facilitate and support communication, social, and functional development. During the COVID‑19 pandemic, when instruction has been remote for many schools, having an in-person intervener for students who are Deaf-blind has been essential.

Orientation and Mobility Specialists

These individuals work one‑on‑one with students to help them develop skills to navigate school, home, and community environments.

Teachers of the Visually Impaired and Teachers of the Hearing Impaired

These certified teachers specialize in supporting students who have a vision or hearing impairment. Both provide instruction and support to individual students in communication skills related to the disability, such as braille and ASL. They suggest strategies and interventions that help remove barriers so students can access the curriculum, teaching materials, and physical environment. For students who are Deaf‑blind, it is important that these educators collaborate with each other and contribute to the IEP.

How You Can Be Helpful

In General

- Help find an appropriate professional familiar with deaf‑blindness to conduct and report on a comprehensive cognitive, medical, social, and physical assessment.

- Presume competence to promote growth and independence.

- Wear clothes that contrast with your skin color to help students who have some residual sight to distinguish gestures, body language, and sign language.

- Be aware of field of vision and confine your visual input to that area.

- Identify yourself when entering a space and announce when you are leaving, with voice cues if the student has some residual hearing or tactile cues if not.

- Be aware of your own anxieties, biases, and fears.

In the Classroom

- Define areas of the classroom with braille labels and self‑adhesive bump dots. For children who don’t use braille, try tactile symbols.

- Allow ample response time after asking a question, giving a direction, or assigning a task.

- Use tactile markers for important areas, stairs, and even people. Consider having staff wear lanyards or bracelets with a tactile symbol that will help students recognize them.

- Use tactile schedules and task analyses (a 3‑D printer can help).

- Create a system of touch cues to help students perceive unexpected events. For example, if there is a fire drill, trying to abruptly physically assist a student who is Deaf‑blind can cause confusion, fear, or an aggressive reaction. Teachers, staff, and students should plan a personalized alert system, like drawing a large “X” on a student’s back with a finger.

- Create a comfortable area furnished with sensory items and accessible reading material so students can take a break from the classroom routine or sit somewhere other than a wheelchair.

- Reduce clutter in the classroom, on the walls, and in the halls.

- Use soft, even light, and avoid fluorescent light when possible. Be aware of and reduce glare by using curtains or moving seats.

- Increase contrast to define important classroom areas. For example, doors should contrast with walls and not be left ajar. Experiment with color combinations, like black on a yellow background, and color overlays that may help some students see better.

- Create tactile‑experience books and adapted books with multisensory components.

- Carefully organize lessons and activities for students, and use touch and visual or auditory cues or routines to define the beginning, middle, and end of each lesson.

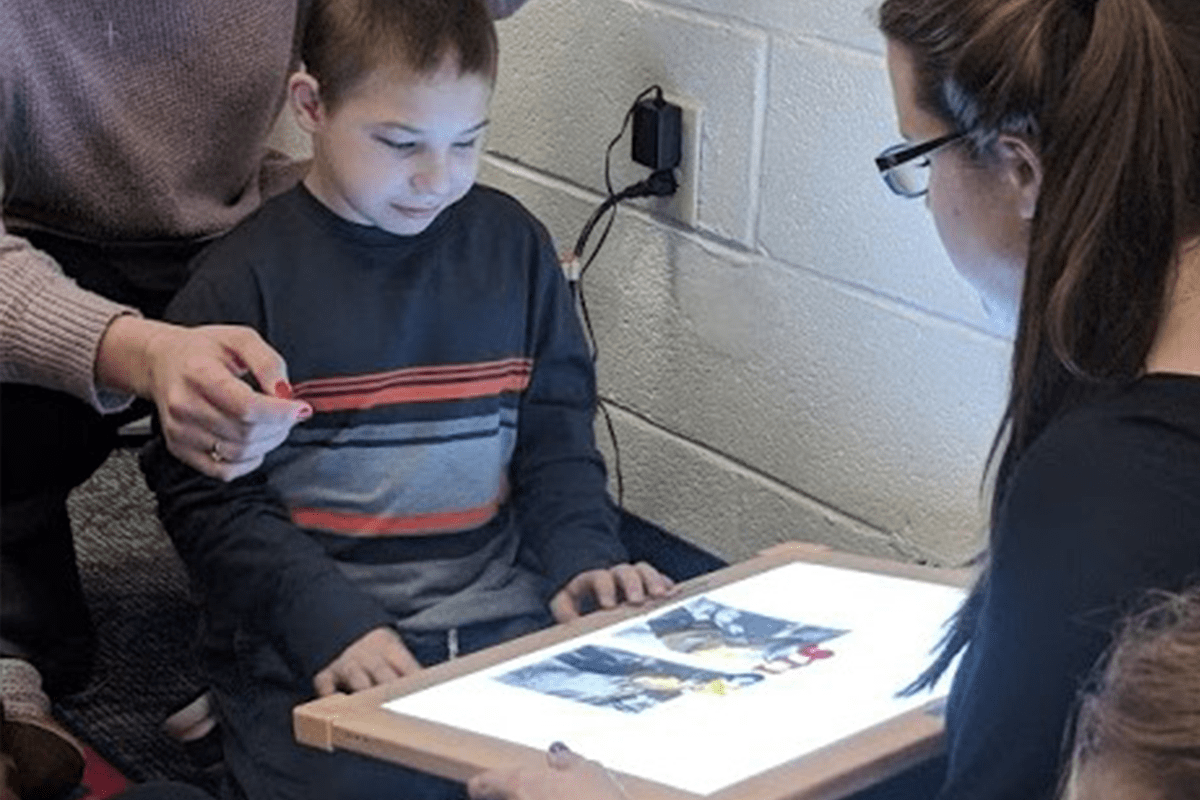

- Use a light box for students who have some vision. It will provide needed contrast and can serve to define the workspace and cue the student when it is time to begin an academic task.

Want to Learn More?

Check out these resources for additional information:

National Center on Deaf‑Blindness

State Deaf‑Blind Projects

Open Hands, Open Access (OHOA): Deaf‑Blind Intervener Learning Modules

Perkins School for the Blind