Children who are learning to communicate using augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) are a diverse group. Some have cognitive limitations and many do not. Some have physical limitations and many do not. Very often, people tend to overlook the group’s diversity and underestimate their abilities or knowledge because the way they communicate is so different.

The Process

Language development begins before a child can speak. While learning to speak, children understand many more words than they can verbalize. Some children who do not have the ability to speak vocally may have the same rich receptive vocabulary as other children but almost no expressive vocabulary, so they cannot share ideas, communicate feelings and ask for things the way most children can.

How does the process differ?

The process for children using SGDs to create vocalizations similar to peers is so much more complex than for children who can vocalize. With a typical child, the process goes something like this: Noah has an idea to communicate, he uses his receptive vocabulary to think of the words he needs and then he speaks the words to the best of his ability.

Sarah uses an SGD to communicate and that process goes something like this: Sarah has an idea to communicate, she uses her receptive vocabulary to find the words but then she must think about what symbols go with those words. There may not be a symbol on the device to go with every word she wants to share. If there is not a symbol for a certain word, she has to revise her thought to include a known symbol. After she comes up with the symbol to use, she has to think about where that symbol is on the device. Then, through pointing or eye gaze, she selects the symbols, and sometimes has to go through several screens to find them. She strings the symbols together to make a phrase.

The cognitive load for children like Sarah and my grandson is much greater than that of typically speaking children. In fact, this process more resembles writing than speaking! We do not expect children to be able to write until well after they learn to speak, but this is the reality for many children who use SGDs to communicate.

Why does the process matter?

It can slow down conversations, which can cause people to lose patience, not give enough time for responses, avoid continuing a conversation or make assumptions about the speaker based on the speed of the responses. I want my grandson’s peers to see him as a potential friend, and I want teachers to see his capacity to learn. I know that might be a challenge because conversations with him will require people to understand that the process of speaking can take longer for him, but he still has important things to say.

How to Help

Wait time

We are lucky: This year Joey had a phenomenal teacher who made her students see that Joey is part of the class, that he can answer the questions she asks and that he has a cool computer to help him talk. She always includes him in activities, calls on him often and gives him the wait time he needs to answer questions. Giving those few extra seconds of wait time is probably one of the most important things we can do to support anyone using AAC, yet moments of silence can be hard for some teachers and even parents. Their tendency is to fill in moments of silence or answer for the child. This is disheartening to the AAC user and can result in learned helplessness. When the teacher models patience and acceptance, it can result in peer acceptance, increase the potential for richer relationships and support real inclusion.

Perspective

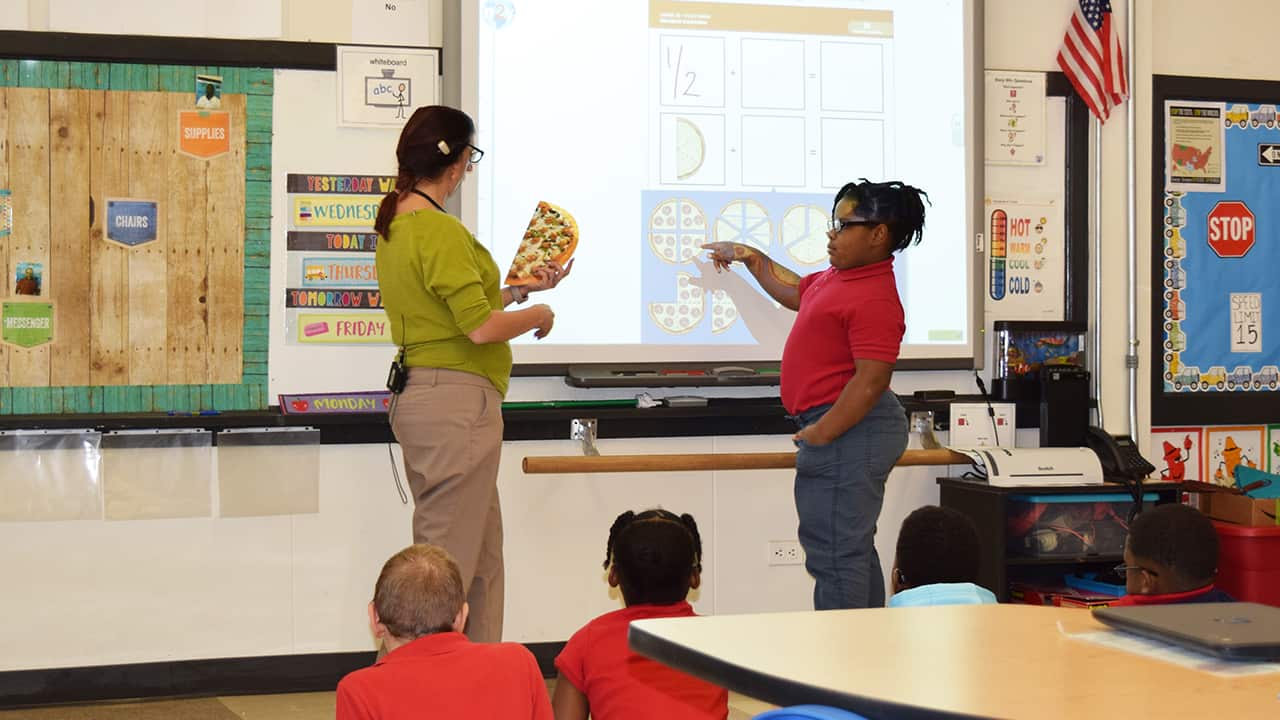

In the classroom, it is up to the teacher to demystify the process of talking with someone using an SGD. Introducing the child and their device and explaining why they use a different type of voice is a good start.

Parents can help by providing information about what their child likes, is good at and their unique characteristics that people appreciate. Peers will discover that they may be different in the way they communicate, but they are alike in other ways.

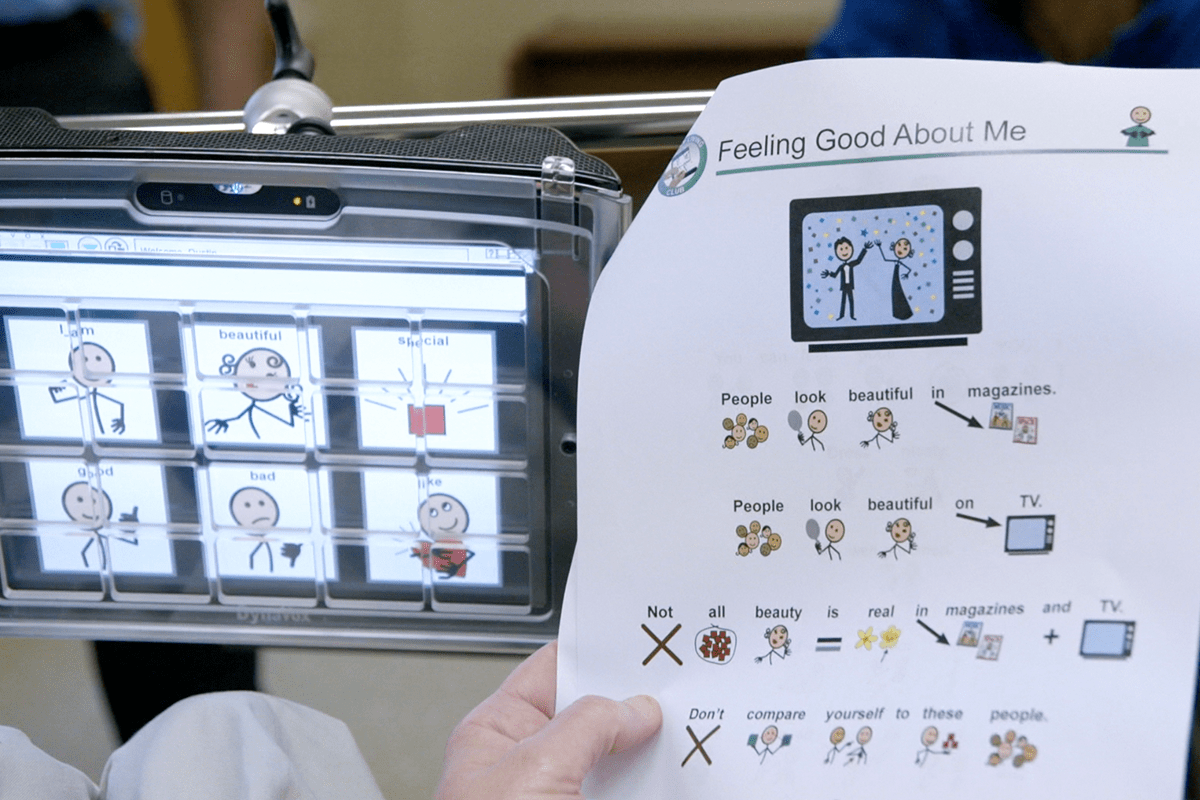

Teaching peers the meaning of some symbols the child uses to communicate and posting them in the classroom can help make peers feel comfortable, facilitate conversation and support the child using AAC. Images that communicate are appealing to most children and adults. There is a reason that emoticons are so popular!

Simulations can help improve understanding and increase patience. Try using the text-to-speech feature on your phone instead of talking for a few hours. You will see how frustrating the process can be. Using eye gaze is even more challenging and tiring. This exercise can go a long way toward helping classmates and family members understand and accept the need to sometimes wait and be patient when communicating with someone using an SGD.

Greater immersion

When children learn to communicate using a comprehensive SGD, it is like learning a second language. The output is the same as the language everyone else speaks, but it is translated from the symbols on the device. Some say immersion is essential to truly learn a new language. Unlike spoken language and sign language, symbols for words are not used by peers, family members, teachers or therapists in everyday communication. So there is no true immersion for children using this type of AAC.

Teachers can help by modeling using the device when speaking with the child and using the symbols when teaching. An extra, inexpensive AAC device for the whole class to use can have the surprising secondary effect of motivating students who are hesitant to speak in class while making the practice of communicating differently less intimidating. Family members, especially older siblings, can be encouraged to learn the system and even take turns using the device during one-to-one conversations.

Teachers, SLPs and parents should be more fluent in the language of the device than the child who is learning to use it. This requires time, patience and sometimes training. We cannot fully immerse AAC learners in their new language, but we should be aware of the need for as many people to embrace and use that language as possible.

Social communication

Creating opportunities for natural easy conversation helps children build relationships, improve AAC use and understand the nature of social communication.

Most kids like to text grandparents or other family members. Sometimes we forget that children using AAC would like this experience too. It wasn’t until someone suggested texting with my grandson that I realized the opportunity we were both missing. Some high-tech SGDs have the capacity to text, which allows the child to communicate directly from the device.

For some, video conversations with the child as they use AAC will be the easiest option, and some children will be able to use the phone itself. These might require a scheduled time so the child can prep by having a message ready. Texting a question, a joke or just a word, emoticon or picture allows them to be a conversation partner in the same way their peers are.

One of my grandson’s teachers reminds us that kids are kids no matter how they communicate. Have you ever heard the saying, “Kids say the darndest things!”? They do—and we should remember that kids using AAC can say the darndest things too! Don’t be too quick to dismiss incorrect answers or unrelated comments. It may be their way of making a joke or silly comment or expressing a creative thought.