Play is the primary way children learn and make sense of the world around them. It contributes to their cognitive, physical, and social‑emotional well‑being while also providing meaningful opportunities for their parents and caregivers to engage with them. In fact, it’s so essential to children’s healthy growth and development that the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child identifies play as a fundamental right:

“States Parties recognize the right of the child to rest and leisure, to engage in play and recreational activities appropriate to the age of the child and to participate freely in cultural life and the arts.”

How Is Play Defined?

Research scientists, child psychologists, and education specialists have described the term play in several ways over the years, but the essence of childhood play is any activity or set of behaviors that a child engages in for the purpose of leisure and recreation. In short, play is about fun, self-amusement, and spontaneity. It can be individual or social, regulated or totally free. Play can be sensory based, cognitive, or neuromuscular. Regardless of the specific activity, play is child centered and intended to be enjoyable.

Play and Early Brain Development

Play is critical to the healthy development of children because it helps shape experiences with other people and the world at large. In the early years, the brain undergoes enormous growth. During this time, learning experiences and positive, nurturing relationships promote strong neural pathways in the brain that help a child make sense of, encode, and retain new information. These connections are created and triggered by rich, loving, and safe environments in the context of responsive and playful caregiving.

There are multiple ways to describe the various stages and types of play. In this article, we’ll take a look at the six stages of play for young children, and then we’ll consider some different types of play that are applicable to both younger and slightly older children. All of these stages and types of play are involved in healthy cognitive, physical, and social‑emotional development.

The Six Stages of Play from Birth through Age Five

American sociologist Mildred Parten was one of the first scientists to study child play extensively. In her 1929 dissertation on the subject, she described the six stages of play as follows.

Unoccupied Play

In the earliest months of life, babies engage in unoccupied play by exploring how their arms, hands, legs, feet, and head can move. They start to learn how to hold and manipulate objects and in doing so, begin to learn about gravity. Very young children engage in this type of play learn to observe things around them and prepare for later stages of play.

Solitary Play

The next stage of play is solitary, or independent, play. During this stage, young toddlers mostly play alone. They do not notice or care to play with other children just yet. If there are other children nearby, they are engaged in separate activities. Children engaged in independent play are learning to entertain themselves and sustain attention to tasks of high personal interest. They can explore freely, practicing and eventually mastering important cognitive and motor skills that will prepare them for play with others.

Onlooker Play

Onlooker play is sometimes called spectator play. It’s the stage of play where children observe other children playing. They watch how other kids manipulate toys, stack blocks, move about, and speak or sing. But they don’t play with the other children just yet. Onlooker play is an important way children begin to learn social interaction skills, and it is also considered a preparatory phase for playing with others.

Parallel Play

During parallel play, children play near other children but don’t necessarily interact with them. This is very common in two- and three-year-olds. You may notice a sibling set or pair of toddler friends playing with their trucks in the same room, but each is engaged in their own imaginary world, with a separate set of internally created rules.

Associative Play

Associative play is quite similar to parallel play, with one difference—a child plays near another child and interacts with them only some of the time. In associative play, play partners may occasionally talk to each other or share a toy, but they eventually revert to their own play and games. Many children start associative play at age three or four, though each develops at their own pace.

At preschool, associative play may look like two children painting on the same easel, but little to no communication occurs about what to create or how to coordinate materials. Outside, siblings may ride scooters together, but lack a plan or shared idea of where they plan to go.

Associative play is an important stepping stone toward cooperative play, where children learn to play together.

Cooperative Play

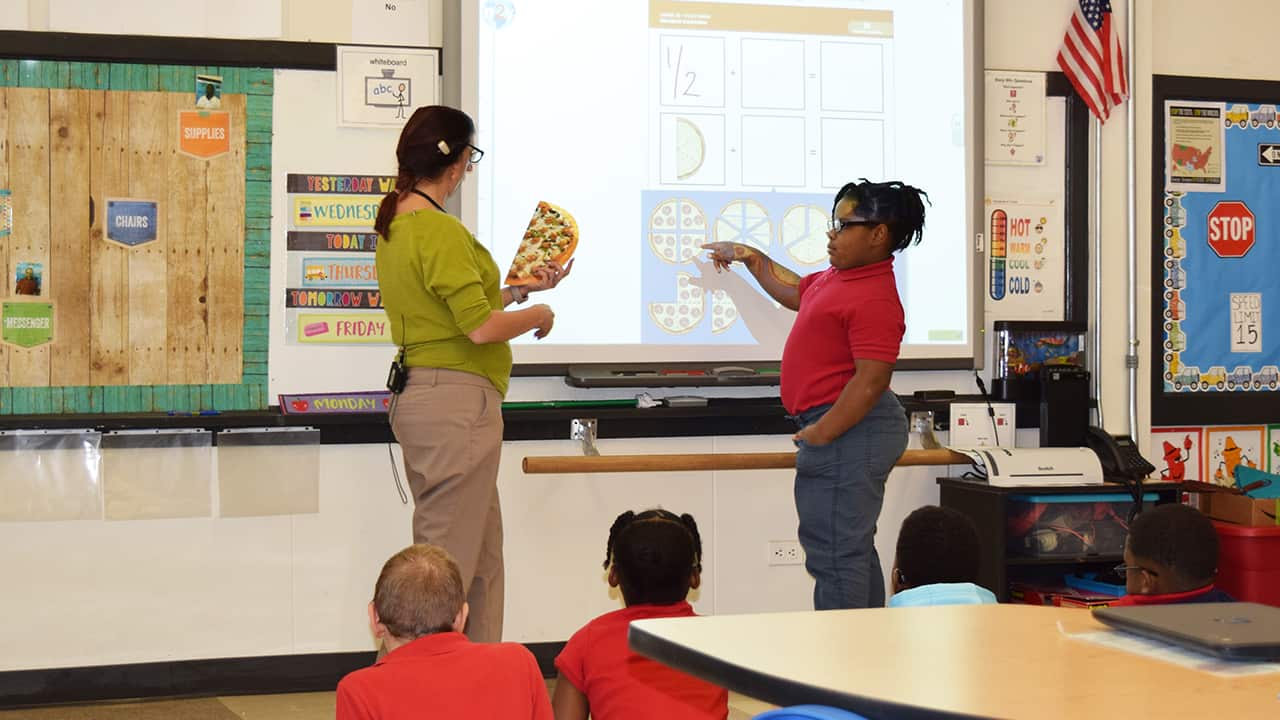

When children work together to solve a problem or achieve a shared goal, they’re engaging in cooperative play. Cooperative play overlaps with several other types of play, including functional play, symbolic play, sociodramatic play, and play with rules. The essence of cooperative play is working and playing together. Siblings and peers who play together in this way may build a fort or a block tower, play a card game, or enjoy a game of tag on the playground, for example. They show interest in the child or children they’re playing with as well as the shared activity.

Cooperative play promotes positive peer relationships and encourages prosocial behaviors like taking turns, helping others, respecting others, and sharing. This type of play also helps children learn to communicate their ideas more clearly, and doing so helps each child in the play group understand their role and enjoy the play experience more fully.

Other Types of Play

There are other ways to characterize play beyond the six stages that primarily describe a developmental, age-based progression. Functional play, symbolic play, dramatic play, and play with games that have rules are other important ways for children, mainly preschool and older, to engage with one another.

Functional Play

Functional play is when children use toys and objects as they are intended to be used. For example, a ball is understood as a ball and used to roll, bounce, kick, or throw. A child with a toy train pushes it along the train tracks and makes the “choo choo” sound. Functional play helps them understand the nature of a thing—if it is fast or slow, hard or soft, big or small. Children use their senses to explore toys and objects and engage with their playthings by concentrating on their intended purposes. Functional play contributes to their cognitive and social growth.

Symbolic Play

Symbolic play, also called pretend play, is when children use an object to represent another object. Before children begin to engage in symbolic play, a stick is just a stick. (This is functional play). As symbolic play develops, a stick becomes a magic wand, a sword, or anything else a child can imagine. Symbolic play encourages them to use ideas and actions to represent other ideas and actions. A child may run down the hallway with a Matchbox car in hand to represent a fire truck racing to get to a burning building, or perhaps distribute wooden blocks to stuffed animals to symbolize serving lunch to friends.

Symbolic play typically begins at about 18 months—this is when young toddlers begin to understand that one thing can represent another thing. At about age two, a child begins to act out sequences of symbolic play, like bathing and then dressing a baby doll. In preschool and beyond, symbolic play becomes more complex, detailed, and social.

Symbolic play contributes to:

- Language development, especially expressive language to represent the thoughts, feelings, ideas, and concepts of the play

- Executive functioning skills, like planning, organizing, and completing tasks (e.g., deciding which stick from the yard will make a good magic wand, planning when and how to initiate its power to turn a rock into a flower, and following through with the plan)

- Social-emotional skills and social interaction (e.g., exploring the relational dynamics between stuffed animal friends)

- Increased creativity

Dramatic Play

Dramatic play is when children assign and accept roles to act out. This kind of play encourages kids to pretend to be something or someone else. When they “play restaurant,” for example, they assign themselves the roles of waiter or waitress, chef, and/or customer. Depending on their ages and depth of imagination some children may also include the roles of restaurant owner, valet parking attendant, happy customer, upset customer, or delivery driver. Many children enjoy a version of this sort of play on the playground. A scene might play out like this:

Child 1

“I’ll have chocolate ice cream, bananas, and pizza, please!”

Child 2

“Okay, that will be five dollars.”

Child 1

“Here you go!”

In this scenario, one child might hand another one rocks or sticks to “pay” for the food, and the food might be “served” on an imaginary dish.

Dramatic play promotes social-emotional development in children, especially empathy. It helps kids learn to put themselves in someone else’s shoes during their playtime, which makes it easier and more familiar to do so in real life.

Games with Rules

Playing games with rules requires advanced cognitive and social-emotional skills like logic, reasoning, and self-regulation. Children engaged in games with rules generally must follow the rules for the game to work. For example, two children playing hide-and-seek must take turns hiding and seeking and must agree to play the role of the hider or the seeker when it is their turn. Children playing a card game, board game, hopscotch, or any type of team sport are playing games with rules. To engage in this way, they must practice some degree of self‑restraint.

Play in a Nutshell

Children experience the world and make sense of it through play. Play is not just an appropriate way for children to engage in the classroom and home environments—it is essential. It is the very foundation of learning, creativity, and self-expression. Indeed, Fred Rogers was right when he famously said:

“Play is often talked about as if it were a relief from serious learning. But for children, play is serious learning. Play is really the work of childhood.”