There are multiple phases involved in learning a social skill, and different types of knowledge and thinking are used throughout the process. These include declarative knowledge, procedural knowledge, and abstract thinking.

Three phases in learning a social skill

It can be helpful to consider the types of knowledge involved throughout the learning process for students receiving social skills instruction. We can then identify which type of knowledge or thinking is required and adjust our teaching and plan instruction and strategies accordingly. The following types of knowledge increase in complexity and are all required for mastery of a social skill.

1. Learning foundational information

Foundational information is fairly straightforward. It includes the recall of specific facts, rules, or characteristics associated with a skill. This can be labeled “declarative knowledge” because it is easy to state this information verbally (to declare it). Because this knowledge consists of concrete information, it can be easier for people with autism to comprehend than abstract ideas. Although it is not limited to memorization, this type of knowledge is often easier to learn for students with autism, who have good memorization skills.

Examples

- Memorize the meaning of slang words and idioms.

- Picture the physical characteristics (body language, facial expression) of a person who is angry.

- Memorize the rules for behavior in a library.

- Remember and recall different strategies that can be used to start a conversation (as opposed to reading them in a graphic organizer).

2. Learning how to perform the social skill

This involves demonstrating the foundational knowledge and often requires the use of motor skills and cognitive strategies. It can be labeled “procedural knowledge.” Good compliance and imitation skills and the ability to discriminate help students become successful with this type of knowledge.

Examples

- Role-play the steps in joining a conversation.

- Classify facial expressions into different emotion categories.

- Identify which person in a picture or video is using a relaxation technique.

- Predict whether a certain comment or response will be well received by a peer.

- Demonstrate calming strategies like deep breathing/calming breaths, counting, muscular relaxation techniques, etc.

3. Learning social competence

Social competence is the most difficult part of learning social skills and involves the most abstract thinking on the part of the student. Social competence builds on declarative and procedural knowledge and requires conditional, or problem‑solving, knowledge. It is the ability to use a skill successfully in a natural environment, across diverse settings, with different people, and under a variety of circumstances. This is also known as generalization, and it is the ultimate goal in teaching social skills.

Examples

- Analyze a social situation and adjust behavior accordingly.

- React calmly to an unexpected change that causes anxiety and/or anger.

- Work in a group with people who express different ideas.

- Recognize the need to use a conversation repair strategy, choose one, and continue the conversation.

- Use socially acceptable behavior while on a date.

- Ask and answer unexpected questions in a job interview in a professional manner.

Social competence requires the ability to choose appropriate strategies and the flexibility to react to ever‑changing and unexpected social scenarios. Understanding the perspective of others, overcoming the need for sameness, and handling the anxiety associated with social interaction can be constant challenges to achieving social competence.

Present These Steps As a Guide

- Recognize the situation and the need for a reaction.

- Think of the best skill or strategy to perform.

- Perform the action for the skill or strategy.

- Evaluate how the action was received by the other person; check your emotions and physical state, if necessary.

- Repeat.

Interventions that can help students learn social skills

The following are some interventions that can be helpful to students at different stages in the learning process.

- Visual supports and representations

- Cognitive behavioral strategies

- Video modeling and self-modeling

- Thought bubbles

- Comic strips

- Social narratives

- Social stories

- Pros/cons lists

- Mnemonic devices

- Relaxation techniques

- A coach, mentor, or safe person

- Self‑monitoring

- Self‑reflection

- Journaling

- Peer mentors

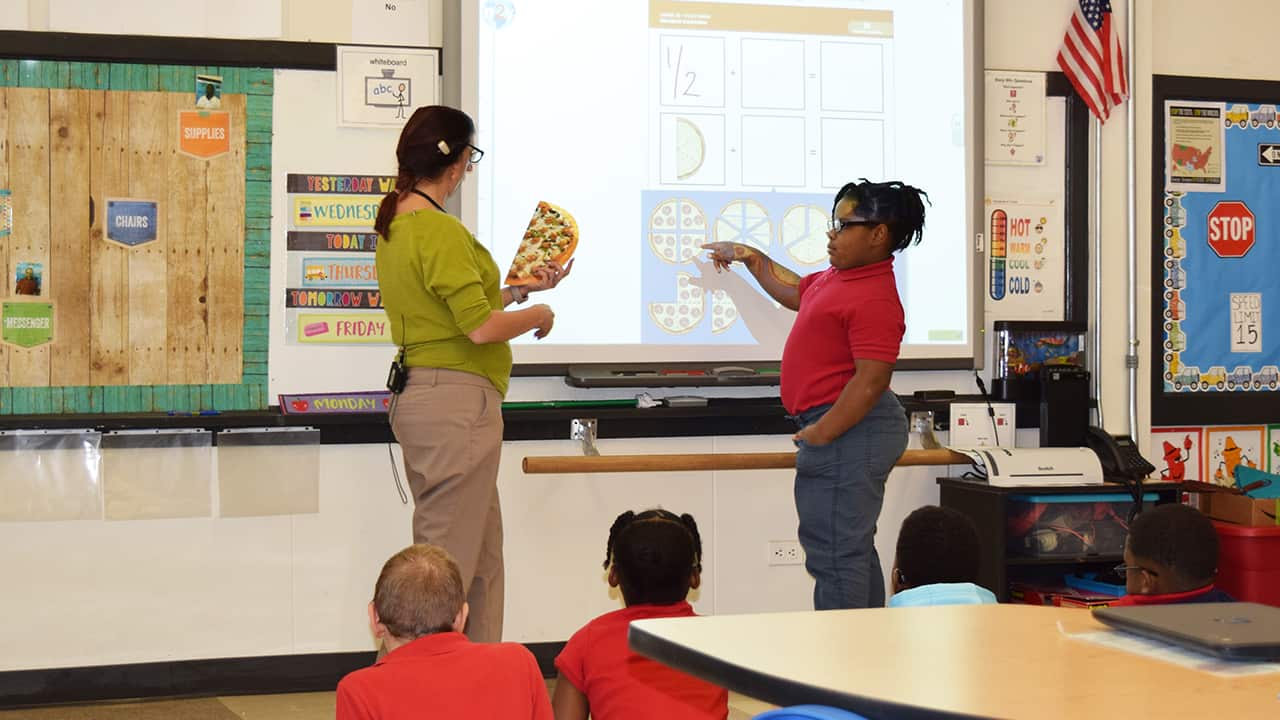

Steps for teaching a social skill

Students with autism may need well‑thought‑out, explicit instruction to effectively learn and practice a new skill. The following steps encompass the three levels of knowledge and can be a helpful guide in planning social skills instruction:

- Define the skill.

It may be necessary to teach vocabulary or break down certain skills into discrete steps to create a task analysis. - Model the skill.

Consider video, peer, and teacher modeling. Use narration to provide a clear explanation of what is being modeled. - Provide a rationale for learning the skill.

Establish student buy‑in. Explain how this skill can make life better. - Have the student role‑play the skill.

Provide supports and encourage self‑talk when needed. - Provide performance feedback.

Be clear and specific with suggestions for improvement and include reinforcement for correct performance of the role‑play. - Assign independent practice.

Provide decreasing levels of prompting and monitor progress. - Set up opportunities for generalization.

Use the natural environment and provide constructive, concrete, and specific feedback.