Books can ignite imagination, provide an escape from the pressures of reality and help us learn. The act of reading to a child can foster a strong emotional bond between adult and child. When children read books on their own, their feelings of independence increase and they can experience a sense of control. When books and stories are readily accessible to all who want them, many positive outcomes are possible.

Yet, for some children the experience of reading a book or even being read to is not memorable, enjoyable or even easily attained. For some people there are barriers to using one or more of their senses; they have trouble emotionally relating to a person, place or activity; or they may have a cognitive deficit that prevents them from processing or understanding what they read or hear.

We remember and learn things more effectively when there is a multisensory element attached. Effective teachers use a multisensory approach when introducing literacy and teaching reading to students because it cements learning and promotes meaningful participation. They pair reading with emotion to enhance the experience.

By using a multisensory approach to create adapted books, we can remove barriers and make reading accessible to all children and adults. When given equal access to the reading experience, everyone can feel pride, confidence and a sense of inclusion.

What are adapted books?

Adapted books are books with supports to make them more accessible and understandable for all learners. Just as there are unique learners with a wide variety of barriers to accessing books, there are myriad ways we can alleviate or remove those barriers to make materials more accessible. For example, we can address those created by deficits in one of the senses by adding elements that activate the other senses, letting all students access the same stories and texts.

In this blog article, I will discuss some ways you can adapt books or other reading material. This is by no means an exhaustive list! Adaptations range from those that provide physical access to those that help with interaction, comprehension or motivation to attend to the story. Here are some examples:

- Material added to provide stabilization for physical access and help with independent page turning

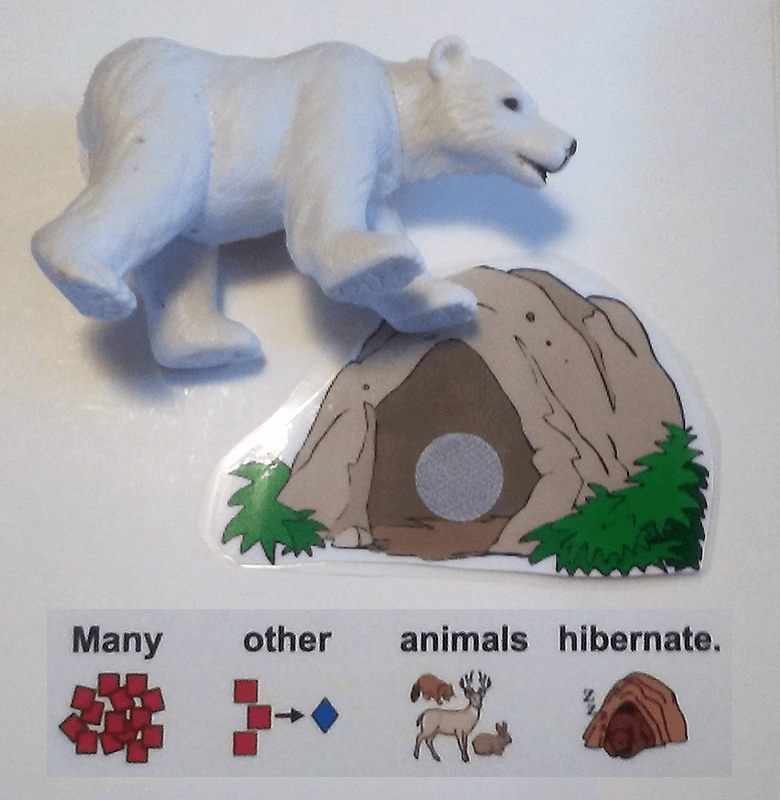

- Adapted text and symbol-supported versions of reading material that help teachers scaffold material and make it more accessible for all

- Changes made to increase contrast or reduce visual distractions on pages

- Providing props like puppets or toys to introduce and accompany a story

- Including picture symbols aligned to speech-output devices to promote word identification and facilitate use of a speech-generating device

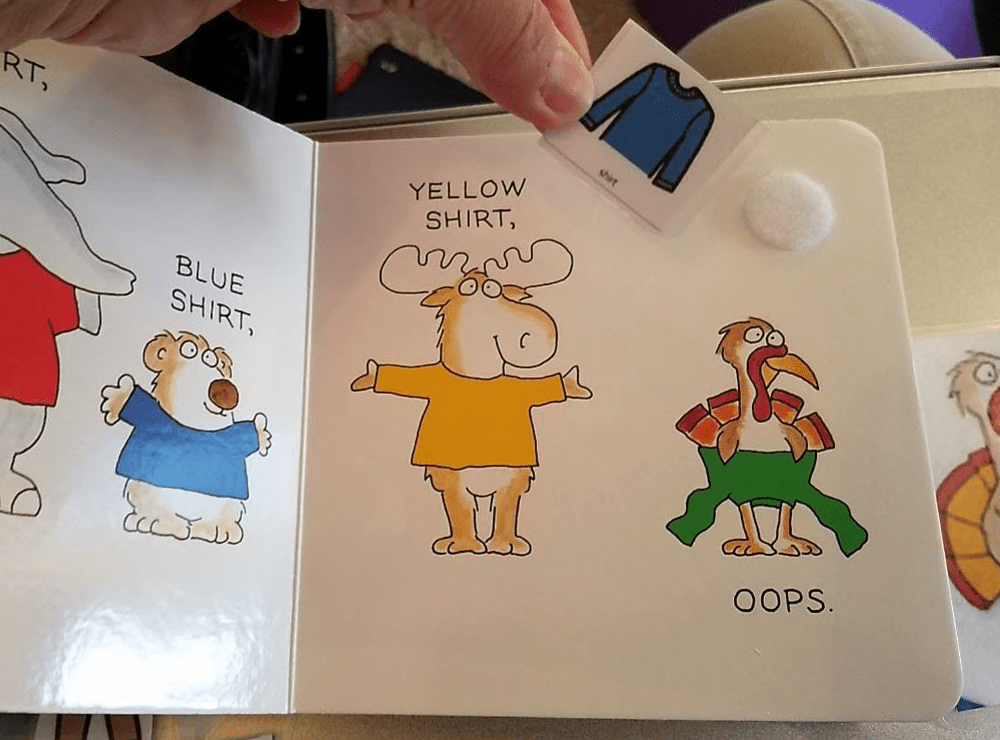

- Adding removable, laminated copies of images or characters from books to support interaction with and comprehension of the story

- Adhering fragrant objects to pages to support multisensory engagement

- Using speech-generating devices aligned to the text to support interaction and understanding of the story

- Adding textures to emphasize images and provide tactile input

For copyrighted books, adaptations that change the images or text can be made for learners with disabilities, as long as there is a hard copy that accompanies the adapted book. Some adaptations create permanent changes to the books. For this reason, it is better if the books are owned by the school, teacher or parent. Other adaptations do not permanently change the book and can be used to enhance a book that is borrowed.

Who benefits from adapted books?

Reluctant readers

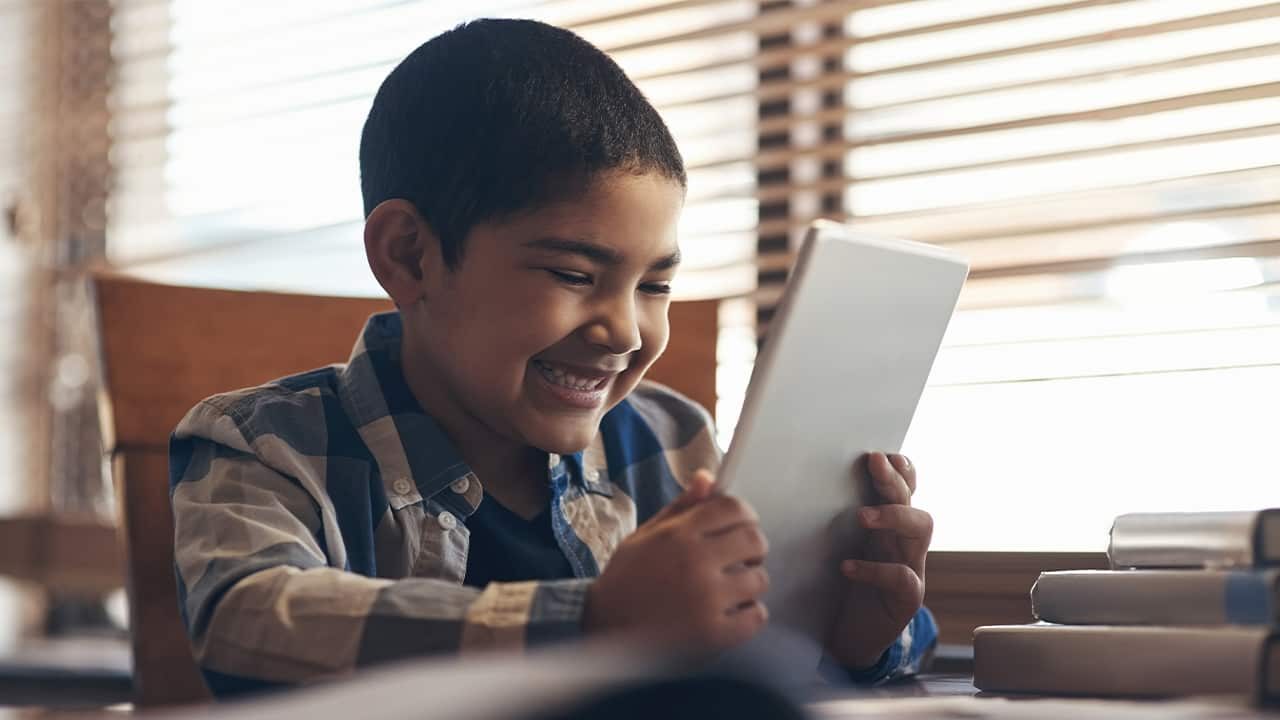

When students are active participants in reading a story or choosing reading material, they are more motivated to read. Some students who feel that they are poor readers often want to avoid the act of reading altogether. Age-appropriate books adapted to the student’s reading level with appealing topics and meaningful illustrations can help encourage reluctant readers.

Students with communication needs

Students who have trouble with expressive language may struggle to ask and answer questions or to make funny, serious or interesting comments that are a crucial part of the learning experience. These students might be using alternative and augmentative communication devices (AAC) ranging from high-tech speech-generating devices to no-tech eye-gaze frames or choice boards. Adaptations can help them become active participants in reading, allow for more effective inclusion and increase self-esteem.

Children with complex bodies

Some children may have limited movement, or may have involuntary movements that interfere with their ability to hold a book, turn the pages or keep from knocking a book to the floor. Providing these children with as much control of the physical book as possible promotes exploration of the environment, independence and choice making. For young children, these are all important developmental skills that foster learning.

Struggling readers

Some learners are not able to comprehend text as it appears in age-appropriate books about topics that interest them. This could be due to a cognitive or reading disability or a visual processing disorder. Students with disabilities affecting reading should receive instruction that is linked as closely as possible to the instruction their peers without disabilities receive. Instruction in concepts like inferencing, determining main idea, author’s purpose, vocabulary and analyzing texts is necessary for all students.

Children with visual impairments

These children often need adaptations to the images to increase size or contrast in order to make sense of illustrations.

Students with unique instructional needs

Students with multiple disabilities, deaf-blindness and complex cognitive impairments usually require significant adaptations in more than one area to give them physical and cognitive access to books.

How can I make adaptations?

For physical access

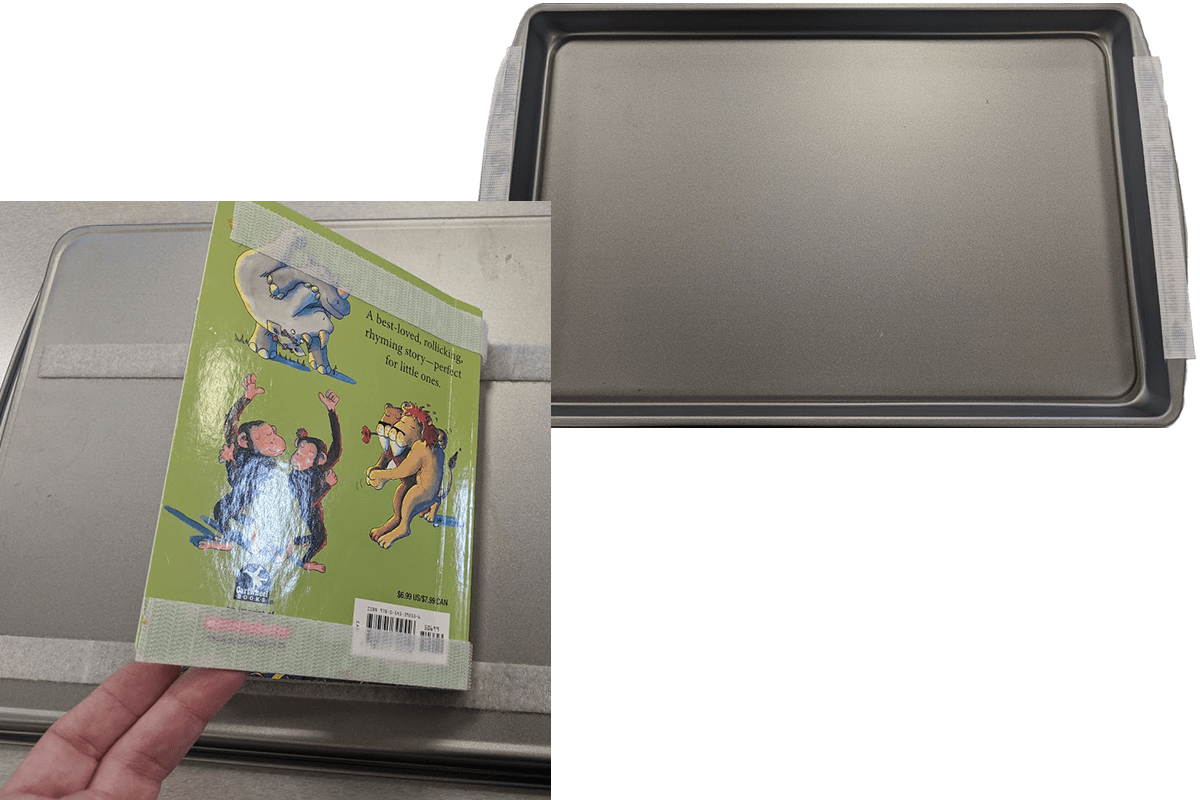

In order to prevent a book from being knocked to the floor and to allow for page turning, stabilize it using Velcro with a metal cookie sheet. Hold the sheet horizontally and apply two strips of self-adhesive Velcro across the middle of the sheet. Next, place the rough Velcro on the book. This allows the book to stick to the cookie sheet. It then should be adhered to the child’s tray or table with more Velcro or clamps.

The cookie sheet can be used to stabilize a book when adhered with the lip side down but can also be used with the lip side up for other activities, including those involving magnets. The lip provides a boundary that prevents items from being accidentally brushed off the work area.

Page fluffers are adaptations that increase the space between the pages of a book, allowing a child with fine motor deficits to better manipulate and turn the page. Page fluffers can be made from self-adhesive Velcro (soft side), foam core or other small materials that are clipped or glued to the outer edge of the pages. Adhere the first fluffer to the top corner of the page and place each subsequent fluffer in a slightly lower position than the previous page.

Some students, particularly those with cerebral palsy, have difficulty grasping traditional paper pages in books. To add weight and rigidity to the pages, cut them apart, laminate them and then rebind them. Some books for young readers are available in a board format, which is ideal. Another option is to cut out images and texts and adhere them to pages in a blank board book.

For AAC users

For students who use speech-generating devices to communicate, reading is a much more complex task. Not only must they identify a printed word with an idea, but also they need to identify an icon associated with a printed word and an idea. To facilitate this process, add symbol support in the same language as the device the student uses. Choose one or two key words from each passage, book or chapter. Print out the icons for these words and glue or clip them to several pages that feature that word. For emerging AAC users, core words are important to learn and should be the first icons to include when adapting books.

For readers with low vision

Children with low vision need books that are adapted to increase contrast and size and to add multisensory features. As long as you use the original book or it accompanies the adapted book, you can replace busy backgrounds with a solid color and add texture to better define objects or characters and enlarge important visual elements. Consider outlining some objects on a page with glue from a hot glue gun or removable wax Wikki Stix. You can attach real objects to the pages.

For struggling readers

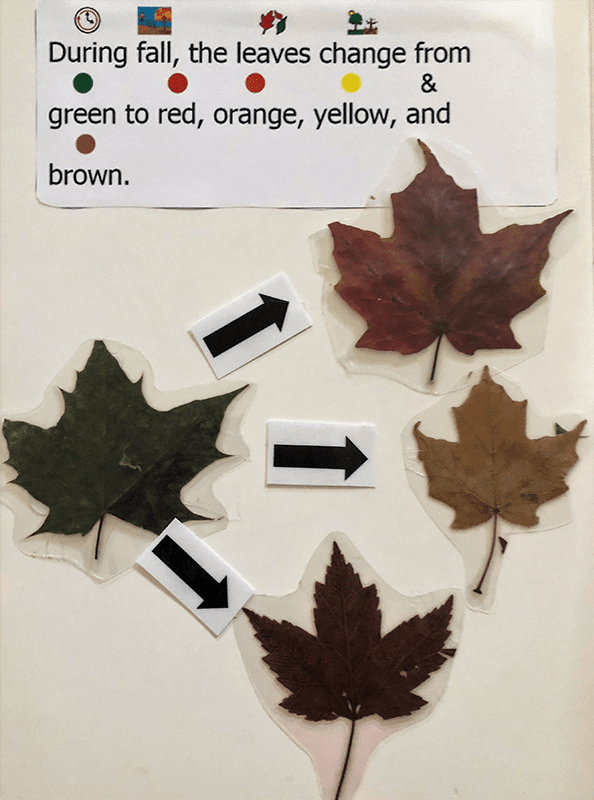

Common adaptations for struggling readers include simplifying the text, adding more meaningful illustrations and using symbol-supported text. Some students will need symbols for each page; others will benefit from a meaningful illustration or two added to certain passages.

To begin making these adaptations, carefully examine sentence structure and vocabulary. Decide how you can retain the meaning of the passage using smaller, clearer sentences and known vocabulary. For some, you may need to copy passages, cut them out and glue them to a page or blank book that includes more white space and additional images.

As children enter the middle and high school grades it becomes increasingly challenging to find appropriately adapted reading material. You can adapt materials yourself, but there are also some commercial options available, including high-interest/low reading-level texts and adapted classics. For example, n2y’s Classics—an add-on to Unique Learning System—offers adapted and symbol-supported texts and interactive activities for grades 6–12.

For engagement

Using props to introduce a story and ask questions during and after reading is extremely motivating, entertaining and engaging for all readers. Puppets or toys can facilitate social interaction and create positive emotions for children. We know that pairing an activity with a strong emotion helps to gain and maintain attention and cement lasting memories. You can create your own two-dimensional, removable replications of characters or objects from a story that can be held by the reader. These can be copied directly from the book, laminated and adhered to the page with Velcro.

An adaptation that is important but often overlooked is adding a scent. Our sense of smell is closely linked to our memories, and fragrance can be a powerful tool to draw and keep attention and make the reading experience more meaningful. Fragrance works for many children with or without disabilities, but for children with limitations in one or more of the other senses, smell becomes extremely important.

Using a Ziploc bag to store fragrant items is an easy way to keep the smell contained until it is time to interact with it. Never use a scent without first checking with the parents of individual students for allergies or sensitivities.

Final thoughts

When we pair reading with multisensory elements, we create a more powerful learning experience. It is important for all children to participate in the act of reading and listening to stories, literacy instruction and social interaction to the greatest extent they are able, but providing equitable access to all students can sometimes be a challenge. Adapted books are an important accommodation that opens doors to learning for many children with unique needs.